Peter Christensen Germany and the Ottoman Railway Network Art Empire and Infrastructure

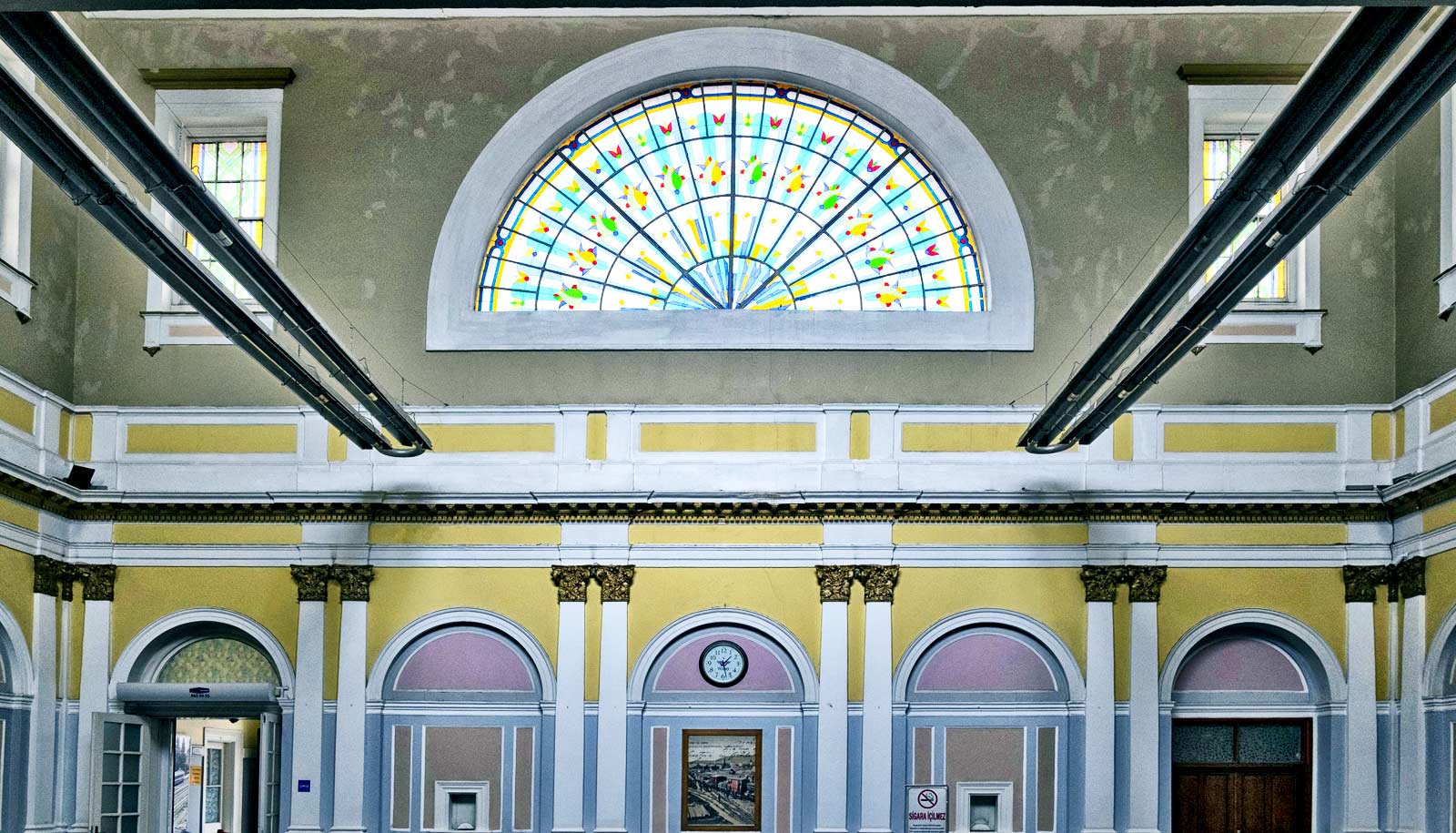

Alsancak railway station in Turkey. (Credit: Getty Images)

Infrastructure deserves a place in architectural history non but as engineering science, but likewise as art, argues an art historian's new book.

Expect at a map of roads or railroad tracks—the winding lines suffuse the terrain similar veins in a body. That's no blow, because "they are the stuff of life," writes Peter Christensen, an banana professor at the University of Rochester.

"Infrastructures make empires."

Trained as an architect too as a scholar, Christensen is the author of a new book—Germany and the Ottoman Railways: Art, Empire, and Infrastructure (Yale Academy Press, 2017)—that considers globalization through the lens of an immense civil works project that spanned cultures and borders in the tardily 19th and early 20th centuries.

While buildings may be the glamorous figures in compages, "infrastructure is what modernizes usa," Christensen says.

"Infrastructures make empires," he declares on the book'due south kickoff page. "The economical, social, and cultural systems of empires are guided by and given form and purpose through canals, bridges, tunnels, ports, and, perhaps most importantly, railways."

And the construction of infrastructure is, at many levels, a collaborative 1, crossing boundaries to take advantage of expertise and finances, and reliant non just on the vision of architects and engineers just of local laborers, likewise.

Key elements of blueprint—the form of the windows, for case, or the rock carving—were the handiwork of workers beyond the multicultural Ottoman Empire.

"There are multiple layers of authorship involved in the creation of buildings and all the other objects that go into engineering a railway network," says Christensen, who has too studied a similar try in western Canada.

Conceived of by the Ottoman sultan, the railways of the Ottoman Empire—which encompassed the lands of what are now Syria, Lebanon, Turkey, Iraq, Israel, and Greece—were largely a German project in engineering, materials, and finances. But the human relationship between the two empires was always an cryptic one. While the German Empire was a rising ability during the Ottoman Empire's reject, and the railway project was characterized by the international printing as a colonial one, with Germany at the helm, the connexion was more dynamic than combative, Christensen argues.

Christensen'south enquiry uses facial-recognition technology to identify ways the stations congenital by Ottoman Empire workers diverged from the original plans created by German language architects.

He finds testament to the cross-cultural nature of the endeavor in fabric artifacts of the Ottoman railway, including train stations, maps, bridges, and monuments. High german architects created standard designs for the railway stations based on the size of the towns' populations. But he didn't meet such replication when he studied the stations that were actually built.

Instead, he found that key elements of design—the course of the windows, for instance, or the stone etching—were the handiwork of workers across the multicultural Ottoman Empire, laboring in different environmental weather condition and drawing on their own cultural aesthetics.

"This is a moment that crystalizes globalization in architecture," Christensen says, "because styles are conflating freely, ideas and models of architecture are traveling and being changed."

How the British empire seized and stole tea

His book is part of a larger projection that as well involves 3D imaging. He and his research squad have used 3D scanning to map precisely where the various Ottoman railway stations differ, zeroing in on the contributions of on-the-ground laborers, who typically effigy fiddling in architectural history.

Few of the images that fill his book have been published before, but Christensen says the importance of the Ottoman railway continues to reverberate in gimmicky life. "As recently as 100 years ago, the borders of these now geopolitical hotspots were completely different—and this railway was meant to connect these disparate lands," he says. "Afterwards Earth War I, the border between Syria and Turkey was fabricated by the railway line—information technology was an arbitrary line in the proverbial sand.

"We alive with the subsequently effects of the creation of these networks to this day."

Source: University of Rochester

0 Response to "Peter Christensen Germany and the Ottoman Railway Network Art Empire and Infrastructure"

Post a Comment